|

|

|

|

||

|

Corpus Domini |

||

|

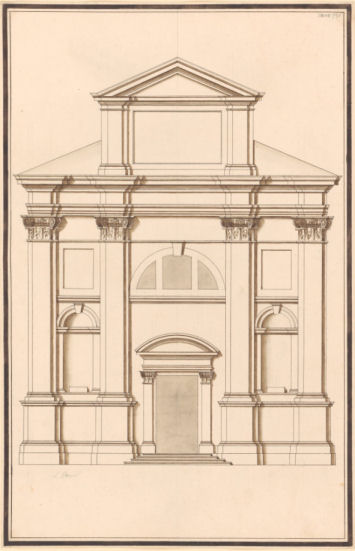

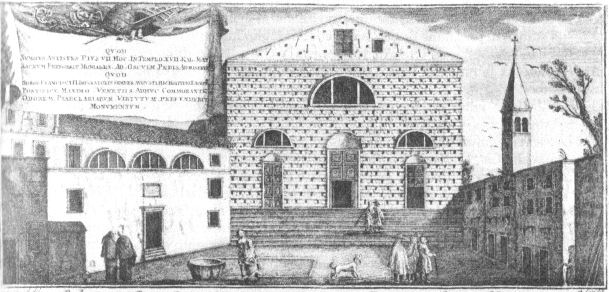

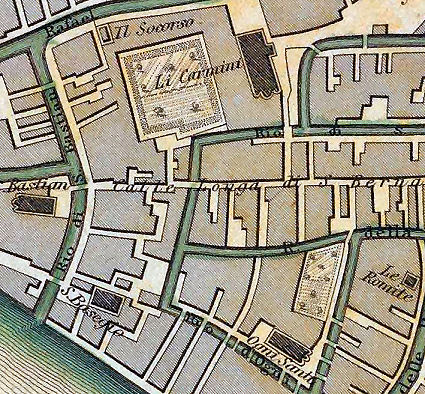

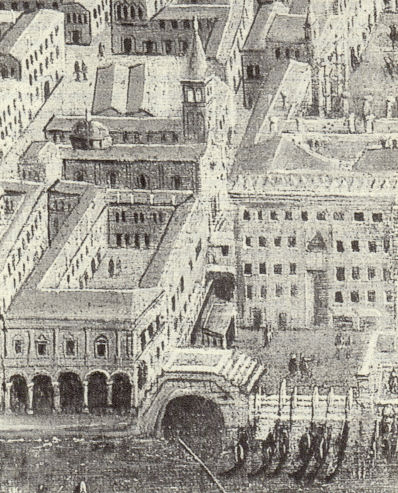

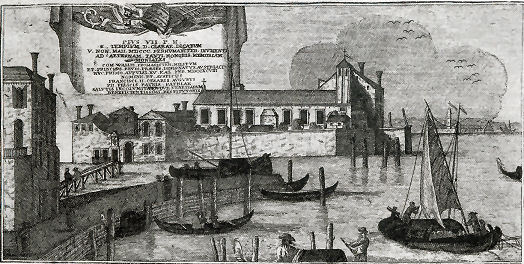

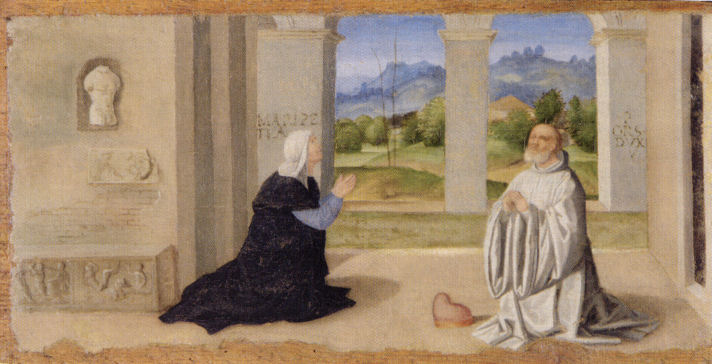

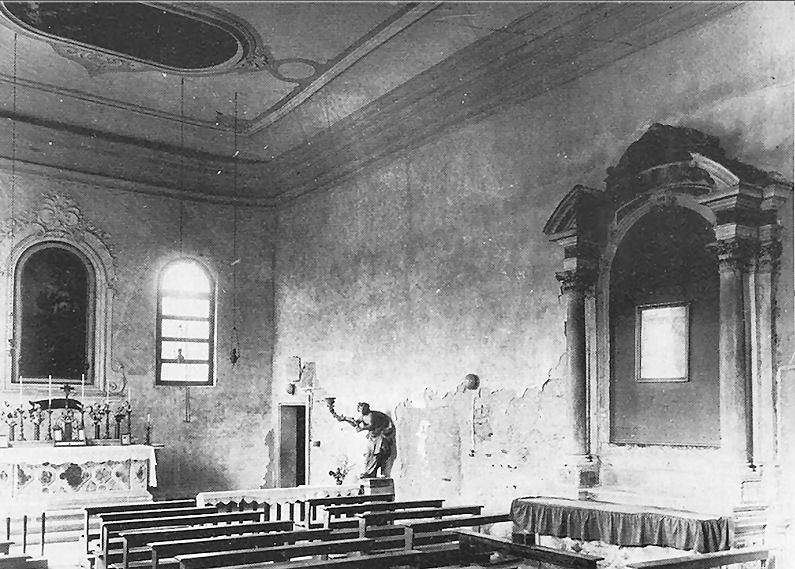

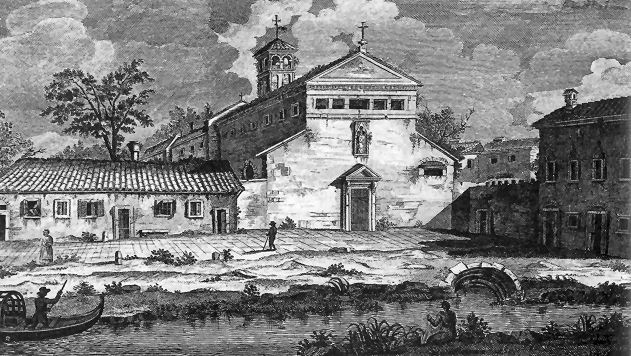

History Established by the abbess Lucia Tiepolo who had grown up in the Benedictine convent of Santa Maria degli Angeli on Murano from the age of 11. After thirty-four years she was made abbess of the unattractive and declining convent of Sant'Apostoli on the lagoon island of Ammiano. After three grim years there she unsurprisingly had a vision of Christ, bound to a column and bloody, telling her to go to Venice and found a convent in his name. Within six years she had found some land on the northwest tip of the city and built a wooden church. At first she'd been hindered in her intentions by four women promising to help and then pulling out, but money she'd earned healing the sick was used instead. Of the four women who got cold feet one developed a tumour on her face and died, one married and was murdered by her husband, one 'burned herself up' and the fourth 'fell into great poverty' and also died miserably. A little later she obtained funds from the young patrician Francesco Rabia, and built a small stone church to replace the wooden one. He also helped her to build a seven-cell wooden dormitory. The building of the stone church was preceded by a vision in which the Virgin came to Sister Lucia and caused snow to fall in the church 'enough to cover an altar' which then froze solid. It remained so for seven days and so this was where the altar was placed in the new stone church. Soon afterwards two devout young orphan girls, aged 15 and 11, Isabetta and Andreola Tommasini, 'had some beautiful visions' . Their confessor, Giovanni Dominici from San Zanipolo, had had similar visions and, after initially suggesting that they merely become nuns at Sant'Andrea della Zirada, encouraged them to help establish a convent at Corpus Domini. He also helped to obtain papal permission for this. Dominici had been appointed by Raymond of Capua, who had been Catherine of Siena's confessor and had become the Dominican master general, to oversee the building of Dominican friaries which adhered to a more faithful, called Observant, version of the Dominican order. The Sienese reforming friar Tommaso Cafferini was charged with their spiritual direction, and he it was who commissioned the works from the also Sienese Andrea di Bartolo mentioned below. Lucia Tiepolo agreed to become the first priora of the convent they now built, and to change the order from Benedictine to Observant mantellate Dominican. The girls' dowries were used for the construction of a new church and a substantial convent that was consecrated on June 29th 1394. It took just a year to build and during that whole time it never rained on a workday, we are told, only at night and on holidays. The complex was damaged by the great storm of the 10th of August 1410, during which the campanile fell into a dormitory, and was destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1440, with reconsecration in 1444, with the financial help of Fantin Dandolo (a Venetian who became Bishop of Padua in 1448) and Tommaso Tommasini, the brother of Isabetta and Andreola, who was bishop of Feltre. The body of Saint Lucy was put in Corpus Domini during the late 1400s, while the Augustinians were carrying out building work at Santa Lucia nearby. But it was is Corpus Domini for so long that the nuns began to consider it their own and were very unhappy about letting it go. So much so that in 1476 a little commando unit of nuns stole the body from the convent of Santa Lucia and brought it back, hiding it under some stairs. Even a delegation from the Council of Ten did not succeed in getting the nuns to reveal where the body was. So they ordered the doors and windows of Corpus Domini to be walled up until they let their hostage out. When the builders arrived, the nuns gave up the body. The Convent of the Penitential Sisters of Saint Dominic in Venice, as it was then called, the church and the kitchen gardens were demolished, after suppression in 1810 to make way for railway offices. A façade model and the print (above right) are in the Correr museum. The Canaletto (right) has the wall of the Corpus Domini complex on the left with the also-demolished church of Santa Croce over the canal just beyond. A different view by the same artist in the Woburn collection has more of the wall but no Santa Croce. Bibliography Sister Bartolomea Riccoboni - Life and Death in a Venetian Convent: The Chronicle and Necrology of Corpus Domini Edited and translated by Daniel Bornstein Contains biographies of around fifty women who died in the convent between 1395 and 1436. Historical events are covered, but also the stories of lives lived behind a triple-locked door, characterised by fasting, hair shirts, chains, whips and miraculous visions. Much of the detail in the history above, and the quotes, come from this book. |

|

|

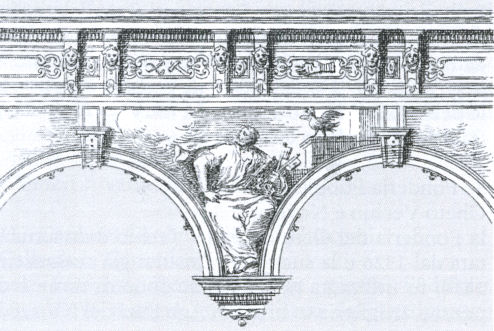

History There had been a church on this site since 1192, probably. The church and attached convent had originally been dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In 1280 the remains of Saint Lucy were brought here from San Giorgio Maggiore to which they had been brought in 1204, looted from Constantinople. (Although the monks there kept an arm.) The church at the time had been called La Nuntiata, after the Annunciation, and its dedication would only be changed to Santa Lucia in 1343, when restoration work was carried out. The church passed from the Dominicans to Augustinian nuns in 1476. Disputes between the nuns here and at Corpus Domini over Saint Lucy's remains (see above) were finally resolved with Santa Lucia's Augustinians getting the remains and the Corpus Domini Dominicans getting 40 gold ducats. In 1579, after paying her homage to the saint, empress Maria of Austria was given a small piece of Lucy's flesh, which is now kept in Vienna. The original gothic church (visible on the De' Barbari map, with its apse-end facing the Grand Canal) was rebuilt in 1580-90 following Leonardo Mocinego's 1565 initial commissioning of Palladio to design a chapel for his family, along with its altar. This church had a classical façade (see right) and changed its orientation to face the canal. Proof of Palladio's involvement has never been found, but it is often assumed. The façade is closest in design to the Zitelle, which is itself a problematic attribution to Palladio. In 1592 the choir and the capella maggiore were completed, and Saint Lucy’s relics were then transferred from the convent to the chapel. The church was finally consecrated in 1617. The nuns were removed in 1806 and Saint Lucy's remains were transferred to the church of San Geremia. The complex was demolished during the 1840s by the Austrians to make way for the railway station of the same name, which was itself replaced by the current station in 1954.

Campanile |

|

|

|

Santa Maria Nuova |

||

|

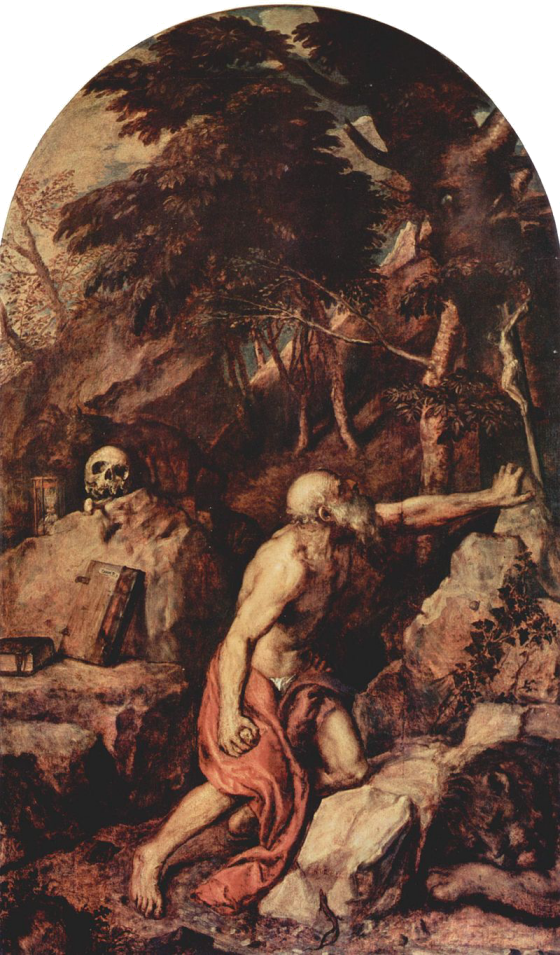

History Built around 971, by the Borselli familly, with the first documented mention in 1110. Originally dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, it became known as Santa Maria Nova in the 13th century. The church fell down in 1535, was swiftly rebuilt, and then restored in the 18th century, with the façade finished by Giovanni Vettori in 1760. Doge Niccolò Contarini was buried here in 1631. Closed in 1808 and then used as a warehouse, its art and ornaments were dispersed and the remains of those buried here taken to the ossuary island of Sant'Ariano. These remains included those of the philosopher Fortunio Spira, the Wocowich-Lazzari family and Doge Niccolò Contarini. Conte Widman bought some bits of the campanile, which had been rebuilt after collapsing in 1488 and was demolished in 1839, for use in some houses he was building in Casselleria. The church itself was demolished in 1852. Although I have a guidebook of 1904 which says it was then being used as a magazine.  Lost art Titian's large and late-style Penitent Saint Jerome of 1556 (see right) is now in the Brera in Milan. It was commissioned by a merchant from Cologne called Enrico, more commonly known as Rigo Helman, his name appears as Elman R in an inscription on a book propped up in the painting on a rock below a skull. His marriage to Chiara d'Anna produced eight children, she being the sister of Titian's friend and wealthy patron Giovanni d'Anna, which may explain how such a modestly wealthy and minorly important merchant came by a Titian of such quality. It sat on his family altar, the first on the right, which after one of his sons, called Jerome, died prematurely was dedicated to his name saint. Helman was accused of fraud in 1561, probably unjustly, and fled Venice, never to return. Vasari says that Titian also painted for this church a little altar-piece of the Annunciation. Jesus Between Saint Peter and John the Baptist by Rocco Marconi from the 1520s, moved from the church to the sacristy here in the 18th century, presumably following the restoration work, then to the Accademia in 1812, where it remains. Local lad In the nearby Campo di Tiziano is the House of Titian, where he lived from 1531-1576. The church in art The Church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli and the apse of Santa Maria Nuova by Bernardo Bellotto (see above right). Also a similar small portrait-aspect view of the back of the Miracoli church, with the circular apse of Santa Maria Nova to the right, is in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight. Santa Maria dei Miracole e Santa Maria Nova by Ippolito Caffi takes a similar viewpoint too. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

1. Sant'Antonio di Castello |

||

History Built from 1346, the first stone was laid by the founder, Fra Giotto degli Abbati, a Florentine nobleman and prior of the Canons of Saint Anthony. Vincenzo and Girolamo Grimani commissioned a new façade in 1518 from Tullio Lombardo, shown in the Luca Carlevarijs print (see right). The tombs of two doges were to be found here - Antonio Grimani, who died in 1523 and Pietro Lando who died in 1545.The monastery and church passed to the Laterans until they were suppressed in 1768. One of the three churches demolished in 1807 by Napoleon to make way for the public gardens, this one seems to have been the greatest loss. Two of the church's bells were sold to help pay for the under-funded project and materials from the church were used towards another building, which was demolished to make way for the Biennale buildings later in the 19th century. The Doric arch of the Lando chapel of the church (designed by Michele Sanmicheli) still stands forlornly in the Giardini Pubblici (see left) and is all that's left of the fabric of the three demolished churches. In Sir Francis Palgrave's Hand-book for Travellers in Northern Italy of 1842, the author wrote that the creation of the Giardini Pubblici 'afforded an excuse for pulling down a few churches which in itself was a recommendation for the French.' Lost art/The church in art Two altarpieces by Vittore Carpaccio - his Vision of Prior Francesco Ottobon of 1512/13 (see right) which depicts the interior of this church with Carpaccio's own altarpiece of The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians on Mount Ararat of 1515 (which is also now in the Accademia, in Room 2) which was later installed over the Ottobon altar of 1512 to celebrate the vision, but appears here anachronistically. The Vision... depicts the miraculous appearance of the 10,000 martyrs to the prior Francesco Antonio Ottobon in the nave of the church in June 1511 during prayers during a time of plague-enforced quarantine for the convent. The screen to the left (or barco) is an example of a once-common, but now rarely remaining, feature in Italian churches and votive offerings can be seen attached to the beams between the arches - models of ships and strips of wax. In May 2022 this painting still had a label saying it was by an anonymous Venetian artist of the 16th century. Conservation work in 2006, during which much overpainting was removed, had largely dispelled these doubts. The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand Christians on Mount Ararat (see below right) was installed over the Ottobon altar, which had been consecrated by the Patriarch Antonio Contarini in 1512, at which time he had also installed into it some relics of the Ten Thousand Martyrs. He may also have played a part in the commissioning of the altarpiece. The site of the Ottobon altar had previously been occupied by a gilded altarpiece depicting Saint Ursula and her 11 Thousand Virgin Martyrs. The blank entrance wall visible in the Vision of Prior Francesco Ottobon was soon to acquire more paintings by Carpaccio - an Adoration of the Magi and an altarpiece of the Resurrected Christ commissioned by Patriarch Contarini for his own altar in the early 1520s.  The Accademia has the large and impressive Polyptych with the

Annunciation of 1357/9 by Lorenzo Veneziano at the end of

Room 1. It's known as The Lion Polyptych after it's

commissioner Domenico Lion, a member of the Venetian senate in 1356/7,

who is pictured kneeling in miniature to the right of the Virgin in the central panel.

It is Lorenzo's first known work but to get such a prestigious commission

he must have painted enough to become established.

The altarpiece has an unusual inscription naming the frame-maker, Zanino,

who may be the same Zanino de Vigna employed in 1363 to help build the

Rialto Bridge. The Accademia has the large and impressive Polyptych with the

Annunciation of 1357/9 by Lorenzo Veneziano at the end of

Room 1. It's known as The Lion Polyptych after it's

commissioner Domenico Lion, a member of the Venetian senate in 1356/7,

who is pictured kneeling in miniature to the right of the Virgin in the central panel.

It is Lorenzo's first known work but to get such a prestigious commission

he must have painted enough to become established.

The altarpiece has an unusual inscription naming the frame-maker, Zanino,

who may be the same Zanino de Vigna employed in 1363 to help build the

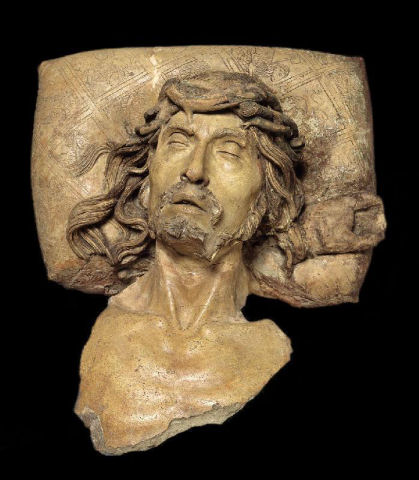

Rialto Bridge.Some very expressive heads from a terracotta sculpture group by Guido Mazzoni (see left) once part of a figure group to be found in this church are now in the City Museum in Padua. |

|

|

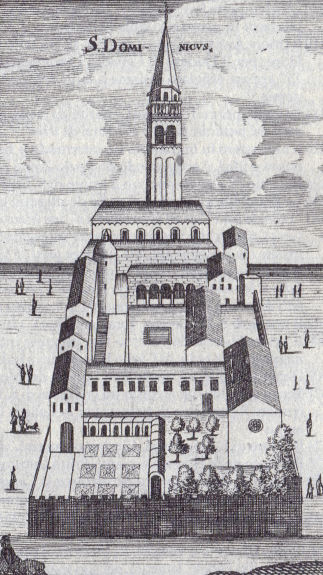

History The monastery and church was founded in 1312. The church was restored in 1506 and 1536. Following the Arsenale fire of 1569 the complex was rebuilt in 1586 and the church reconsecrated in 1609. The court of the Inquisition was held here until 1560 when it moved to the Frari. Prohibited books that had accumulated were burnt on the 29th April and the ashes tipped into the canal that is now the Via Garibaldi. Given to the Austrian navy in 1807 and soon after demolished, it being one of the three churches demolished to make way for the Giardini Pubblici, San Domenico faced the (still standing) church of San Francesco di Paula across a canal that was filled in to make the Via Garibaldi. A bridge named after San Domenico was lost too. The bridge and San Bartolomeo (the previous church on the site of San Franceso di Paola) are also visible in the de' Barbari map of 1500 (see far right) beyond San Domenico in the top left-hand corner. The former (early 15th century, Gothic) entrance to the monastery is to be found on the south side of the Via Garibaldi at no. 1310 (see right). An engraving by Thomas Astaler from 1687 Lost art Savoldo's c.1538 Annunciation, painted for a chapel planned by Antonio Massa, whose decoration was finalised by his nephew, is now in the Accademia, or the Museo Civico, Pordenone. A painting on canvas of Saint Paul by Carpaccio from 1520 was first recorded in the church of San Domenico in Chioggia in 1783, where it remains. It may originally have come from this church. |

|

|

History The church attached to a naval hospital, built in the aftermath of Venice's victory at the Scutari. The first stone of which was laid in 1476, with the church consecrated on 25th March 1503. Minimal rebuilding in the following centuries, it retained Renaissance appearance, its dome and three altars. One of the three churches demolished by Napoleon to make way for the Giardini Pubblici, but it is said to have fallen into disuse as a church long before. Lost art A bas-relief by Tullio Lombardo, now in the patriarchal collection. Amongst the altarpieces were an Annunciation by Francesco Vecellio , now in the Accademia and a Resurrection with Saints Nicolò and Giuseppe by Pietro Ricchi, now lost. The main doorway was removed and reused in the Accademia buildings. The church in art |

||

History A church founded on the island of San Daniele (see top left in detail from Ughi map of 1729 below) in 820 by the Bragadin family. First certainly documented in 1046, the church was given in 1138 to Manfredo, a Cistercian, and he built a monastery, consecrated in 1219. In 1437 the Augustinian nuns from Sant'Andrea de Zirada moved here. They replaced Benedictines and were established here by Chiara Ogniben Sustan, the new community's first abbess. The Vivarini panel of Saint Clare, mentioned in Lost art below, may be her portrait. The church had a nave and two aisles with rectangular apses. Their were twelve columns of red Verona marble and nine alters. The complex became a French barracks in 1806 and an Austrian one in 1815. When the church was demolished in 1839 the remaining buildings became the college of the Royal Imperial Navy. What's left is still in use as a barracks. Lost art Bas relief of Daniel in the Lions' Den and a 1469 carving of the saint now at the Ca'Bragadin (Bigaglia) in Barbaria de le Tole.  Two panels depicting female saints (one is an elderly Saint Clare, the other unidentified) of c.1485 by Alvise Vivarini and Daniel in the Lions' Den by Pietro da Cortona from 1663/4, all three in the Accademia, the latter in the new rooms dedicated to 17th & 18th century religious art on the ground floor which were opened in 2021. The 18th-century guidebook, by Albrizzi, also mentions works here by Tintoretto, Varotari and Leandro Bassano. A detail from the the Ughi map of 1729. |

Above is a detail from the Clarke map

of 1838.

|

|

|

San Sebastiano |

||

|

History A parish church, founded by doge Pietro Orseolo II in 1007, a plague year. It was in Campo San Lorenzo, to the left as you faced the church of San Lorenzo, as seen in the engraving, right, by S. Giampiccoli. Demolished in 1840. |

|

|

|

|

History  Originally built between 811 and 827 and then rebuilt 1053 and after the fire of 1105. It kept this form until it was suppressed on 12th April 1813 and demolished in 1829. The Austrians built a prison on the site, which itself closed in 1929. See the map in the entry for San Provolo above - San Severo is at the top in the middle. Lost art A typical Tintoretto bustling panorama Crucifixion from the c.1557/8 (see below) is now in the Accademia. It was painted for the left wall of the chapel of the Scuola del Santissima Sacramento here. According to Ridolfi, the church fathers had wanted to use Veronese, but Tintoretto had got the job by promising that he would paint it like Veronese, which is probably the explanation for why it is so colourful. It underwent restoration in 2018. Detailed preparatory drawings for the painting can be found in the Royal Collection in Windsor and the Uffizi. The church is also said to have contained (two?) works by Vincenzo Catena.

San Severo, in a detail from the map of 1635,

|

|

|

History Built 1119-1239 by the Celsi family, with a Cistercian convent dedicated to Saint Mary of Heaven, Santa Maria Assunta in Cielo. Carlo Zeno, the hero of Chioggia, was buried here in 1418 by the sailors of Venice. La Celestia was favoured by patrician families, being third only after San Zaccaria and San Lorenzo in its wealth. The convent lost part of its orchard when the Arsenale was expanded in 1564 and then was rebuilt following severe damage during the Arsenale fire and explosion of 14th September 1569, partially to designs by Andrea Palladio. The map (see right) shows how unsurprising it was that a fire in the Arsenale would damage this convent. La Celestia is number 83 (upper middle left) in the 1572 Braun and Hogenberg map, the entrance to the Arsenale is number 133 (bottom middle). Following the fire the nuns were temporarily moved to San Giacomo della Giudecca, inconvenient for the monks there, in their single cloister. The situation was supposed to last six months, but it was almost three and half years before the nuns returned here. The church rebuilding fell to Vincenzo Scamozzi, who planned a domed Pantheon-like structure (inspired by Palladio's rejected original design for the Redentore). Work began in 1582, but was not yet finished in 1603 when the nuns rejected his plans just as the dome was being installed. Having demolished this work in 1606, Scamozzi built them a simpler Latin-cross shaped church, consecrated in 1611. The church was demolished in 1810. The convent was used as Austrian garrison barracks from 1858-76, and as a school for naval mechanics from the Arsenale from 1873-1943. In 1930 part of it was converted into public housing, with the rest used for housing the city archives. The cloister recently underwent restoration.

Lost art |

|

|

|

History Built by Doge Pietro Ziani at the suggestion of Ugolino Bishop of Ostia, who later became Pope Gregory IX, on a visit as apostolic legate in 1224. The Augustinian convent and church were named Santa Maria Nova, to commemorate the church in Palestine destroyed by the Saracens. In 1519 the nuns protested at plans to bring the observant nuns from Santa Giustina here. A wall was built to separate the observant nuns from their unwilling convent-mates, which the militant resident nuns duly knocked down. They got a stern telling off from the Doge and Patriarch, and the wall was rebuilt. After some fires and reconstructions Guglielmo dei Grigi was commissioned to undertake rebuilding between 1547 and 1549. Church and monastery were suppressed and given to the Navy in 1806, becoming a prison in 1809. The choir was demolished in 1822, the remaining parts in 1844. All that's left is a relief (see right), of God the Father with the Virgin and Saints Mark and Augustine, from over the church entrance, which is now embedded in the wall of the Arsenale. The plaque underneath the arch, dated 2nd May 1557, reads... MDLVII ADI II MAZO

Lost art |

|

|

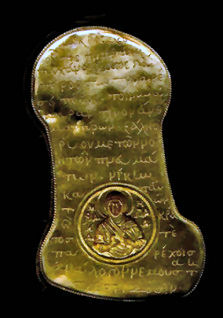

History A church here was founded in 1130 by the Balbi family and originally dedicated to San Liberale and Sant'Alassio. The right hand (used for blessing and the vanquishing of a dragon) of St Margaret of Antioch (known as Santa Marina in the East) was brought here from Constantinople in its reliquary (see left) in 1213 by one Joannes de Borea and placed on the high altar, resulting in the church switching dedication to her. Santa Marina was a 5th century saint from the Lebanon who spent her life as a monk, only being found out as female upon her death, despite her having been accused of fathering a child, which she then raised. One report says that her remains were transferred to Santa Maria Formosa. The (empty) silver-gilt hand reliquary mentioned above and pictured left is now in the Museo Correr. The church had two fine monuments, one to Doge Michele Steno, the other to Doge Nicolò Marcello and the work of Pietro Lombardo. Both are now in San Zanipolo. The church was restored a few times, and rebuilt in 1705, before suppression in 1810. In 1818 it became a tavern, but was demolished in 1820 to make way for housing. The church is commemorated by a small altar with an image of Santa Marina on the wall of a house in Campo Santa Marina. Giovanni Bellini lived in the parish nearby in his later life, probably in Campo Santa Marina itself. |

||

|

History There's still a campo named after this church, which was at what is now number 3026. The church was founded during the reign of Doge Pietro Centranico (1026-1032) by the Celsi and Sagredo families. The remains of San Gherardo Sagredo, martyred in Hungary in 1046, were preserved as a relic in the family chapel to the left of the high altar. He is now commemorated by the Sagredo chapel in nearby San Francesco della Vigna. The church of Santa Ternità was restored in the 13th century, when the body of St Athanasius was brought here. It was rebuilt in the early 16th century, in 1569 (after a fire at the Arsenale), in 1607, and in 1721. The final work was in the late 18th century, funded by the parish priest Antonio Aghen, when the main chapel and the two side chapels were rebuilt. Suppressed in October 1810, it was used as a timber store until it was demolished in 1832. Interior There were seven altars. One of the chapels, which housed the body of Saint Anastasius the Martyr, was very richly decorated with marble, and had a marble Crucifix by Francesco Cavrioli from 1684 which, after the demolition of the church, went to the chapel of Saints John and Paul. Another housed a relic of Saint Gherardo, a monk from San Giorgio Maggiore. He had been born into the powerful Sagredo family and became a missionary in Hungary where he suffered martyrdom on 24 September 1047. The Sagredo chapel itself, the one to the left of the high altar, contained a large, and reportedly imposing, monument to the family. Over the altar was an image of San Gherardo painted by Girolamo da Santa Croce, who had two more paintings originally in the main chapel - a Visit of the Shepherds with The Holy Trinity above in a crescent moon, and a Virgin and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas. A painting depicting the life and martyrdom of Saint Anastasius also by Girolamo da Santacroce, the lower section of a polyptych, the upper elements of which were the Body of Saint Anastasius by Fialetti and the Eternal Father with Angels by Pietro Malombra, may have disappeared well before suppression. Two paintings by Fialetti and another, a partial work by Aliense, completed the decoration of the chapel of Saint Anastasius. In the main chapel there were two works by Palma Giovane - a Flagellation and a nightime Taking of Christ. A Crucifixion, also by Palma, was placed above the door of the sacristy. It is now thought to be the one in the Madonna dell'Orto Lost art Apart from the above, lesser paintings included an altarpiece with The Holy Trinity, a Virgin with Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas and a Madonna of the Rosary with Saints Vincent and Oswald, all by Francesco Maggiotto; Saints Matthew and Mark by Cavalier Bambini and Saints Peter and Paul by Zibellini, the latter placed in the sacristy. Greater works included an altarpiece by Giambattista Tiepolo, with St Francis Receiving the Stigmata, a Coronation of the Virgin attributed to Carpaccio, an altarpiece of four panels by Giambellino depicting Saints George, Peter, Paul and Anthony, and two paintings by Cima da Conegliano, a Virgin and Child with a Bishop and Visit of the shepherds All of these paintings have been lost. The relics of Saint Anastasius and Saint Gherardo  Sagredo are now in San Francesco della Vigna.

Sagredo are now in San Francesco della Vigna.

Campanile

A view by Pivador from

around 1847

|

|

|

|

History |

|

|

History Another of Venice's churches whose dedication looks east, to the Greek-church father of monasticism. Built in the late 9th or early 10th century, and renovated after the fire of 1105, but it collapsed during the 1348 earthquake. Rebuilt 1476 to 1514, with a nave and two aisles, a ship's-keel ceiling and an image of Saint Basil over the altar. Further restoration in the late 17th century. The interior was restored by Andrea Tirali in 1730. Closed in 1810, the church became a timber warehouse before being demolished in 1824. When demolished the church still had its façade of the 14th century, but the interior was more lavish and baroque, in a 17th-century style. A glass-topped coffin housed the remains of the blessed Peter Acotanto which are now in San Trovaso. He was a 12th century Benedictine recluse and sometime resident of San Giorgio, beatified in 1759/60 for his work with the poor, he gave them all of his inheritance, his statue can be found on the façade of the church of San Rocco. The area formerly occupied by the church is now playing fields. Lost art The rich pictorial decoration included, along the sides of thel nave, above the arches, some Stories from the Old Testament by Girolamo Gambaratos and other canvases by Jacopo Palma Giovane, Aliense, Marco Vecellio, (a Last Supper, sold to San Vito d'Asolo in 1839), and Pietro Mera (a Way to Calvary). There were also the Twelve Apostles and Four Doctors of the Church, by Leonardo Corona. Also works by lesser-known artists, such as Camillo Marpegan, Giuseppe Scolari. Bortolo Donati, Bernardino Prudenti, and an altarpiece by Giuseppe Angeli depicting the Blessed Pietro Acotanto Giving Alms. This latter work was purchased first by Don Angelo Ghedini and then by Abbot Pianton for the abbey of the Misericordia. The greatest loss, however, are the organ doors, which depicted two Saints, which were believed to be by Alvise Vivarini. Their fate is unknown. Many paintings went to Bucovina, including a Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes, attributed to the school of Palma Giovane and five Apostles. Antonio Visentini 1771

A detail from the Clarke map 1838, |

||

History HistoryThe original church of the Umiltà was a small oratory about which we know very little, except that it belonged to the Teutonic Knights. In 1525 when the order of Teutonic Knights was suppressed their land passed to Andrea Lippomano, who was a friend of Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits. Work on the new church for the the Jesuits, the first one in Venice, began in 1560. In August of 1563 work on the interior of the church began, including the ceiling by Veronese. Swift enlargement was undertaken from 1578, involving a new choir, extending the apse behind the altar and interior woodwork. This work would've necessitated the moving of the Tintoretto high altarpiece discussed below. The church was finished in the late 1580s and reconsecrated in 1589. Following the Jesuits' expulsion from Venice in 1606 the complex was occupied by Benedictine nuns from San Servolo on 26th June 1615 - they had asked to be moved due to the dangerous condition of their convent. In 1651 the impoverished nuns attempted to sell the Tintoretto Deposition but were refused permission by the senate and ordered to place it in 'a conspicuous location. in the view of everyone'. In 1806 the church and monastery were suppressed and both were demolished in 1824, making way for the gardens for the patriarchal seminary. Campanile Built 1564. Lost art The church had the mighty fine Tintoretto Deposition of c.1562 (see right) which is now in the Accademia. Scholarship has lately come to accept that this painting was over the high altar originally, as suggested by its Eucharistic subject. Recent conservation work (in 2009) has shown that the panel was originally more square, having later had canvas additions of more than 30cms to left and right. Within twenty years of its installation the installation of a new tabernacle here necessitated its moving, first to storage in the sacristy, where it was recorded in 1651, and then to at least two other positions. A Life of the Virgin cycle by Palma Giovane was in the apse. Also three oval ceiling paintings by Veronese, which were installed in the newly-restored Capella dell Rosario in San Zanipolo in 1926, having been in Vienna after being appropriated by the Austrians in 1838, and having had their restitution demanded in 1919. These depict The Annunciation, The Adoration of the Shepherds and The Assumption. The first two, which were cut down in size, probably sometime during the 18th century, would have been over the entrance and altar respectively. The larger Assumption would have been in the centre. Small monochrome scenes showing Moses, Jonah and other Biblical subjects have been lost. The four altarpieces of the 1560s in the nave chapels were an austere Saints Peter and Paul by Jacopo Bassano, Palma il Giovane’s Passion of Christ, The Circumcision by Marco dal Moro, and Simonetto da Canciano’s Saint Francis. The Bassano, one of the few altarpieces he painted for Venetian churches, has been in the Galleria Estense of Modena since 1811, the Moro is in the Accademia, the others are lost. Moro's Circumcision is a rare use of this subject as the main panel of an altarpiece. It features a scroll held aloft by putti with the Latin text And thou shalt call his name Jesus, reminding us that the ceremony included his naming. The church in art Depicted on Odoardo Fialetti’s view of Venice which is at Eton College (see above). The church flank is visible in Canaletto's La Dogana e la riva delle Zattere in the Crespi Collection in Milan. The façade is distantly visible across the Giudecca canal in a view in the Wallace Collection, a detail of which is top right. |

|

|

|

San Geminiano |

||

|

History The original Byzantine church of San Geminiano and San Memma is traditionally said to have been built on the middle of a then-smaller Piazza San Marco around 554 by the eunuch general Narses, next to an orchard belong to San Zaccaria. The first certain documentation dates to 1023. This church was demolished in the 12th century to extend the Piazza - part of major work on the Piazza and the Palazzo Ducale instigated by Doge Sebastiano Ziani. A new church was built further to the west and the Rio di Batario, on which the old church stood, was buried beneath paving. Begun to designs by Venetian architect Cristoforo da Legname in 1505, the church was dedicated to Saints Germinianus and Menna. Work was completed by Jacopo Sansovino in 1557, who contributed a dome and a new façade, as part of his major improvements to the whole piazza. The work was driven by the parish priest Benedetto Manzini and latterly was offered finance by Tommaso Rangone (who became procurator here in 1554) with the condition that his bust was displayed on the façade. This demand was refused by the Senate. (Rangone got his way later with the less-prominent church of San Zulian.) A bronze bust of Rangone by Vittoria was placed in a vestibule over the entrance to the sacristy here, in fact. But pride of place, flanking the high altar, went to the busts of two pievani (parish priests) Matteo e' Eletto by by Bartolomeo Bergamasco and Benedetto Manzini, also by Vittoria. The church was centrally planned around a dome, with aisles ending in small chapels either side of the deeper high- altar chapel, with altars on the north and south walls by the entrance. It was famous for being ornate and covered in marble and Istrian stone decoration. The high altar was probably made during the 16th-century work, to designs by Cristoforo dei Legname, by Bartolomeo Bergamasco. Manzoni seems to have had connections with the Barbaro family, having been elected first rector of the church of San Paolo at Maser, near which the Barbaro family villa was to be built by Palladio and famously frescoed by Veronese. The church was demolished, to no small outcry, to make way for the grand staircase of Napoleon's Palazzo Reale, soon after its closure in May 1807. Since 1797 it had served as a military barracks due to its strategic position. It was originally to be replaced by a triumphal arch. Sansovino was buried in the church but his remains were moved upon demolition to the Seminario della Salute. His children, Fiorenza and Francesco (the latter the author of Venetia, citta nobilissima et singolare) had also been buried in the church. The remains of Saint Geminianus himself were transferred to the church of Santissimo Nome di Gesu. Francesco Sansovino, the son of the church's architect Jacopo, so he may have been biased, described the church as 'being lavishly decorated within and encrusted with marble and Istrian stone on the outside. It is extremely rich and well-conceived in design'. Another guidebook, by Leonico Goldini, said that in comparison with the other churches in Venice it was 'judged by everyone to be almost like a ruby among pearls'. In the Hand-book for Travellers in Northern Italy, a guidebook of 1842, the author, Sir Francis Palgrave wrote that the destruction of San Geminiano was an example of the 'Gallic vandalism ... which has inflicted such irreparable injury upon the fine arts'. Lost art Two panels from an altarpiece by Bartolomeo Vivarini of 1490 once here, depicting Saints Mary Magdalene and Barbara, are now in the Accademia, in the big room XXIII which used to be the upper part of the Carita church. Organ doors by Veronese (see right) commissioned by Benedetto Manzini, along with choir stalls. The organ having been placed over the the door to the sacristy in the left transept, as with the organ doors also painted by Veronese at San Sebastiano. The doors here depicted Saints Geminianus and Severus together in a wide and decorated domed chapel-like space on the outside, whilst the smaller inside wings portrayed two single saints in imitation stone niches - John the Baptist and Menna. All the figures have their bodies facing the altar and are lit from the left where the window was. The face of Saint Severus is a portrait of Manzini. It has been suggested that Saint Menna may be a portrait of the artist, or his brother Benedetto. In the first half of the 18th century the canvas panels were removed from the organ loft and displayed in the church. Having spent time at the Villa Reale at Stra, in Vienna and in the church of San Gottardo in Milan, since 1924 the doors have been in the Galleria Estense in Modena - Saint Geminianus having been a 4th-century bishop of Modena. The bust of Tommaso Rangone by Alessandro Vittoria is now in the Ateneo Veneto. The high altar, with three statues of saints, all by Bartolomeo Bergamasco is now on the high altar of San Giovanni di Malta. The busts of the parish priests mentioned above are in the Ca' d'Oro. An altarpiece depicting Saint Catherine for the Scuola di Santa Caterina by Giovanni Bellini, which was replaced by the Tintoretto, is now lost. Jacopo Tintoretto's Angel Foretelling Saint Catharine of Her Martyrdom (1560-70) (see right) was commissioned by the Scuola di Santa Caterina for their altar, the first on the left, in this church. It was here until the church was demolished in 1807, after which it was transferred to the Accademia, who sold it in 1818, around which time it was acquired by a Colonel T.H. Davies, and until recently was reported to to be in a private collection in Chicago. But this altarpiece has been in the news recently as it emerged that it had been bought by David Bowie in 1983. At the sale very soon after Bowie's death in 2016 it was bought by an unnamed European collector for around €200,000, who then offered it as a long-term loan to the Rubens House Museum in Antwerp. Rubens himself owned seven Tintorettos and Bowie loved the Rubens House Museum, it seems. Across from the Tintoretto, over the first altar on the right, was Saint Helena with Saints Geminianus and Menna by Bernardino da Murano, of c.1510, now in the Accademia The church in art The church appears in Piazza San Marco looking west towards San Geminiano by Canaletto, versions of which are in in the UK Royal Collection and the Gallaria Nazionale in Rome (see detail top right). A similar view by Guardi is in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches.  Bibliography David Bowie's Tintoretto: The Lost Church Of San Geminiano Published by MUVE to coincide with the 2019 exhibition From Titian to Rubens - Masterpieces from Flemish Collections in the Doge's Palace, this is a revised and redesigned version of a book about the painting published by Colnaghi in 2017. The crowd-pleasing title is somewhat deceptive. There is an essay on the church, but it also contains longer pieces on the painting itself, its restoration, and on the connections between Venice and Flemish artists, like Rubens, van Dyke and Maerten de Vos - subjects germane to the exhibition but not really suggested by the book's title. As such it serves more as a second volume of the exhibition's catalogue. Update 22.2.2024 The churches on this page don't often get fresh news to report, but work last year involving the lifting of the paving stones in Piazza San Marco has revealed traces of the earliest church (see right). Archaeologists found fragments of medieval pavement and walls, and a brick tomb containing the remains of seven people from the 7th or 8th century (see left) a child, roughly 8 years old, a woman and five other adults. A better idea of the siting of the first church should now be possible; and remains have been removed for study. We await scholarly developments. |

|

|

|

|

||

History Initially dedicated to San Mauro, founded in 920, with the first documentary evidence in 1069. Later dedicated to Sant'Anzolo, i.e. San Michele Arcangelo. The church burnt down in 1167, was rebuilt in 1431, and restored after another fire in 1685. Domenico Cimarosa, the musician, was buried here in 1801. Closed on the 14th October 1810 and used as a warehouse until it was demolished in 1837. The Altare del Santissimo from this church is now in the right chancel chapel in the nearby church of Santo Stefano. The high altar is in the church in Solimbergo, a village very north of Venice.  Campanile The first one was toppled by an earthquake in 1084. A later detached campanile fell down in 1347 after, it is said, the bells rang out of their own accord. In 1455 an architect called Fioravanti tried to correct a strong inclination and a day later it fell, killing two friars. It was rebuilt in 1456 but struck by lightening in 1487. A restored campanile lasted until the church was demolished in 1837. Lost art Titian's last altarpiece, the dark and smoky Pieta of 1575/6 (see right). The friars at the Frari refused to place it over the altar in the Cappella del Crocifisso, in front of which Titian was hoping to be buried (and where he was in fact buried) and placed it over another altar, so prompting the artist to demand its return to his studio. He never was buried in his hometown, his next plan, and so his intention to have this painting over his tomb was never realised. It was eventually acquired by his ex-pupil Palma Giovane, who made small additions to it and left it to Sant'Angelo, where it was by 1664, seen by Boschini 'on the left hand', and where it remained until it was moved to the Accademia in 1814. The prostrate figure to the right, probably representing Saint Jerome, is supposedly a self-portrait. The church in art The church appears in paintings by Canaletto (see above) and Bella in the Querini Stampalia gallery. |

||

History HistoryIn the 12th century the order of Templars owned the church of Santa Maria in Broglio (from brolo meaning garden or orchard) with an attached hospice for pilgrims on their way to the holy land. It stood on the site of the current Hotel Luna near the Vallaresso vaporetto stop. Abandoned in 1311, when Pope Clement V abolished the Templars, the complex passed to the Knights of Malta, who later sold it to the procurators of San Marco. They rented it to a Fra Malasa on the understanding that he didn't use it to house the poor but keep it available for visiting ambassadors. In the late 15th century the monastery was rented to the Osteria della Luna. Restoration work on the church was begun in 1516 by the confraternity of the Holy Spirit (aka the confraternity of the Ascension) but was not completed until 1597, because of conflicts with the confraternity of the Blind. The church was later renamed after the Feast of the Ascension and closed in 1810. It was used as a warehouse until it was demolished in 1824 to make way for an extension to the Hotel Luna.

|

|

|

|

Santi Filippo e Giacomo |

||

|

History A church and convent was founded here by the Bendictines in the 9th century, with its dedication later extended to include Sant'Apollonia, in connection with the nearby scuola. Restored in 1683, keeping most of the old church intact, then in 1726, the organ, the tabernacle, and the high altar were renovated, with walnut stalls installed all around the nave. The church was suppressed on May 12, 1806, and its furnishings were sold at auction on March 22nd 1808, the sale taking place in the church. From 1830 the church was used as a linen mill. The complex was mostly demolished, the remaining buildings becoming the residence of the primate of San Marco. The lovely Romanesque cloister, dating to the 12th/13th centuries, fell into ruin, but remains (see below right) as part of the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art, following restoration work to convert it for this purpose. Its entrance is facing us to the right of the church façade on the left in the print (see above right). Lost art Most of the paintings here seem to have been of martyrdoms. Among them was an Adoration of the Magi by Pietro Damini, The Martyrdom of Saint Agnes by Santo Peranda, featuring a portrait of Primate Tiepolo who had commissioned it. The Martyrdom of Saint John, from above the sacristy door, was by Fialetti, and The Flight into Egypt "on a long canvas," was by Maffeo Verona, and to be found in the chapel to the left of the main chapel, belonging to the gold merchants' guild. The altarpiece of the high altar was a Dead Christ by Palma Giovane, who also painted a Martyrdom of Saint Justina here. There was a Martyrdom of Saint Isidore by Pietro Gradici from Verona and a Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia was reported here by Boschini and Ridolfi as a work by Alvise dal Friso. A chapel dedicated to Saint Scholastica, documented since the 13th century and probably the remains of an earlier and larger church was completely demolished after the suppression, having been decorated with paintings by Ridolfi. The church was the burial place of Giovanni Stringa, canon of San Marco, who updated Sansovino's Venezia città nobilissima and who died in 1610 at the age of forty

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

San Boldo |

||

History San Boldo is Venetian dialect for St Hubald. The church, originally dedicated to Sant’Agata, was built, according to tradition, in the 10th century. The first documentary evidence mentions the Tron and Zusto families and building in 1088. The church was damaged by fire in 1105 and rebuilt in 1305. This last rebuilding involved enlargement and the building of the campanile. The church acquired the name San Boldo from the attached hospice for poor women founded in 1395 with a bequest from the De Matteo family of Florence. The freestanding church became gradually hemmed in and at the beginning of the 18th century was falling down. Rebuilding resulted, and the church and reopened in 1739, after plans by Giorgio Massari. After the 18th century rebuilding works by Rocco Marconi, Paolo Piazza, Gaetano Zompini and Francesco Pittoni could be found here. Suppressed in 1805, closed in 1808 and demolished in August 1826, only the truncated 14th century campanile remains (see photo right) now attached to the Palazzo Grioni, also sometimes called the Palazzo San Boldo. (However, another source says that this is the Palazzo Businello S. Boldo and that the Palazzo Grimani (aka Grioni?) was demolished.) The church façade was to the right and faced the campo, as can be seen on the de'Barbari map (see below).  Lost art A 14th century relief of Saint Agatha saved from the church is now in the Museo Patriarcale. Above is a drawing of San Boldo from from c.1800 by Giacomo Guardi, left is the church on the de' Barbari map. |

||

|

|

||

History San Stin (or San Stefanin) is the Venetian dialect for San Stefano Confessore, (the Confessor). The original church was built in 936, first documented in 1038, destroyed by the fire of 1105 and rebuilt by 1149. Much work on the interior in the 17th century, with improvement to several chapels belonging to local worthies, including the wealthy Zuane family, who first commissioned Longhena, then Antonio Gaspari, and finally Domenico Rossi. These last two artists oversaw the work on the church.  Suppressed by the French in 1810 and demolished soon after. The base of the campanile and the remains of a chapel still exist, and were used until quite recently as an upholsterer's workshop. The campo of the same name (the church was on the rio side, see the centre of the map detail below San Nicolò below) has a well head with a relief depicting St Stephen.  The church in art In Bernardo Bellotto's Campo San Stin (see left) the church is at the end of the campo, with the Frari looming beyond. Lost art The Assumption from c.1550 by Jacopo Tintoretto now in the Accademia (see right). It went there in 1814, following the suppression and demolition of San Stin, but was loaned to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello from 1928 to 1955. A large Dream of Saint Joseph by Antonio Molinari is lost, but there are drawings in Düsseldorf. |

||

History Founded in 959 by the Bishop of Olivolo, Pietro Marturio Quintavalle, who left the church in his will to the future Bishops of Olivolo. The first documented mention dates it to 1088. Rebuilt twice after fires in 1149 and 1630, in the latter case to designs by Francesco Contin, with consecration following in 1691. This church's interior was described as slender and reminiscent of Longhena. Chapels included one for the Zane family by Antonio Gaspari and Domenico Rossi. Suppressed in 1808, closed in 1810. Used as a flour mill from 1813 (to ease the blockade) and then as a warehouse until it was demolished in 1872. Housing was built on the site. The church is top right of centre in the detail from the the Clarke map of 1838 below. During work to install sewage treatment tanks in 2000 the foundations of the last church were found and then four graves dating from the first church. They had been opened and desecrated by the builders of the second church, and the bones of about 20 other corpses were found all mixed up. Lost art Altarpieces by Bernardino Prudenti (St. Augustine and St. Monica with the Virgin Mary and Jesus), Pietro Libera (The Crucifixion with St. Francis and other saints) Giuseppe Nogari (The Martyrdom of St. Christopher) and Paris Bordone (Ecce Homo).

Local press

The second church, on the de' Barbari map.

|

||

|

History Given the diminutive name San Nicoletto to differentiate the small oratory here from San Nicolò del Lido, both churches dedicated to Saint Nicholas of Myra. Built from 1346 by Procurator Nicolò Lion, the man who discovered Doge Marin Falier's conspiracy in 1355. He had been miraculously cured of a serious illness in 1332 by eating some lettuces from the Frari's friars' garden and so founded this small church and monastery next to the garden and left it to the Franciscans after his death. He died in 1356 and was buried in this church, his tomb being moved to the wall of the chapel of the Santi Francesci in the Frari after the church was closed in 1807. There had been repairs to the original building in 1407 and 1410, and rebuilding in 1561, major redecoration in the 1580s, including the works by Veronese, and reconsecration in 1582. Recent scholarship, however, has this 16th century rebuilding beginning as early as 1512. On the night of the 10th/11th January 1746 a fire swept through the convent. The church and sacristy escaped the worst damage, but the convent's renowned library was destroyed. When the complex was closed by Napoleon in 1806 the monks moved to the Frari, the monastery being used by the French as a barracks for a while and then as a flour mill from 1813 (to ease the blockade). Following swift spoliation, by 1810 the church itself was empty, later to be turned into tenements and demolished. The convent's cloister is now the Frari's third cloister and became part of the State Archives complex in 1875. Lost art Titian's unusual and impressive altarpiece The Virgin and Child with Saints (see right) installed here 1533/35, is now in the Vatican Pinacoteca. The friars sold it in September 1770, for a paltry sum to the British consul John Udny who sold it on the Pope Clement XIV, for a huge profit. The priors excuse for selling their prize work was its poor condition. Part of the deal was that Udny pay for a substitute, and so in 1774 Saint Nicholas Calming the Storm at Sea by Giuseppe Angeli was installed. It's now lost. The Titian shows a selection of Venice's favourite saints (prominently including Saint Nicholas of course) and Franciscans, seemingly in some sort of circular dungeon. The rays above the Virgin's head originally emanated from the dove of the Holy Ghost, in a lunette removed after it was taken to Paris by Napoleon in 1797, and before it was returned in 1816. Titan's employment here may have contributed to his getting the career-boosting commission for the huge Assumption for the Frari. The church acquired eleven works by Veronese in the 1580s, late in his life, including seven ceiling paintings, all displaying his later, darker palette. It is said that the 20-odd paintings created under Veronese's supervision form a coherent cycle on the theme of redemption. Two of the ceiling paintings, The Consecration of Saint Nicolas as Bishop of Mira and Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (see below) are from over the altar and entrance here respectively. Also a wonderful and innovative off-centre Crucifixion, from the right wall of the nave here, 'above the altar of Saint John the Baptist' according to Zanetti. All are are now in the Accademia. Both the ceiling paintings were originally quatrefoil shaped but Saint Nicholas was drastically cut down and made circular to fit the Accademia ceiling panel in the centre of room 1, before 1817. They are now high on the wall of the new Room X dedicated to Veronese, as are two monochrome figures of the Old Testament prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, which originally once flanked the high altar in this church. On the same wall is the off-centre Crucifixion already mentioned All of these works have been dated c.1582.  Five more ceiling paintings went to San Zanipolo and are set into the ceiling of the Rosary Chapel. These are the central Adoration of the Magi and four surrounding L-shaped Evangelists. A single panel continuous narrative by Veronese showing the Baptism and Temptation of Christ, which hung on the left wall of the presbytery went to the Brera in Milan in 1808. Above it was a Last Supper and Washing of the Feet by Veronese’s son Carletto Caliari which went to the Accademia but is now in San Zanipolo. Opposite these two in the presbytery were a Christ in Limbo by Palma Giovane, now in the parish church of Quero in Belluno, with above it a now lost Resurrection by Veronese. Also paintings by the Flemish painter Paolo Fiammingo, also from the 1580s redecoration, and by Nicolò Bambini and Giovanni Antonio Fumiani, the latter famed for the ceiling of San Pantalon. Bibliography |

|

|

History A church called Santa Maria Madre del Signore was founded here in 920 by the Polani and Bernardo families. Santa Chiara was founded in 1236, rebuilt several times, caught fire in 1574, consecrated during rebuilding work in 1620. The Franciscan convent and church were suppressed in 1807, with the convent converted into a military hospital in 1819. All but the 17th century cloisters were demolished in the second half of 19th century. They're now part of the police headquarters and are also home to the Red Cross. The convent in art Canaletto's The Grand Canal, looking South-East along the Fondamenta di Santa Chiara, (Private collection, London), has the wall of the convent peeking into the right-hand edge, with the wall of Corpus Domini, also lost, to the far left. Lost Art  Paolo Veneziano's large Coronation of the Virgin Polyptych of c.1333-45 (see below left) was painted for Santa Chiara during a time when the abbess here was from the Dandolo family. Paolo had also painted the  lunette over

the tomb of Doge Francesco Dandolo, commissioned by his widow. The

polyptych has been in the Accademia since the church's suppression. It

faces you as you get up the stairs into room 1 and has recently undergone

restoration work in the Misericordia workshop. The central panel is flanked by eight scenes, seven from The Passion

plus a Nativity. The six smaller scenes above are four episodes

from the lives of Saints Francis and Clare bookended by two more

Passion scenes. Following the Napoleonic suppressions in 1808,

the central panel went to the Brera in Milan and was not reunited with the

rest of the polyptych, which had been acquired by the Accademia in 1812,

until 1950. lunette over

the tomb of Doge Francesco Dandolo, commissioned by his widow. The

polyptych has been in the Accademia since the church's suppression. It

faces you as you get up the stairs into room 1 and has recently undergone

restoration work in the Misericordia workshop. The central panel is flanked by eight scenes, seven from The Passion

plus a Nativity. The six smaller scenes above are four episodes

from the lives of Saints Francis and Clare bookended by two more

Passion scenes. Following the Napoleonic suppressions in 1808,

the central panel went to the Brera in Milan and was not reunited with the

rest of the polyptych, which had been acquired by the Accademia in 1812,

until 1950.

From

the Merian map of 1635, Santa Chiara is rear centre,

|

||

History Established by refugees fleeing the Lombards maybe as early as 568, becoming a parish church around 775. A monastery was then established here in 1109 by Cluniac monks from France who rebuilt. A scandal forced the monks to leave in 1341. The complex passed to the Franciscans and thereby to the Poor Clares. The nuns offered the site for the building of a church giving thanks for Venice's delivery from the plague of 1575/7, a plan which eventually lead to the building of the Redentore church on Guidecca. Eventually restoration to plans by Antonio da Ponte (the architect of the Rialto Bridge) took place from 1583, the year Doge Nicolo da Ponte laid the foundation stone, with consecration taking place in 1600. Suppressed in 1806, used as a warehouse and then demolished in 1813. The site became the private garden of Spiradone Papadopoli in 1834, but is now the grim and dusty public Giardini Papadopoli. The church had nine altars and was richly decorated. A column from the church (see photo below right) is all that remains, in the corner of the garden wall on Rio dei Tollentini. The black and white photo (below left) taken in December 1928 shows a church-like building which was actually one of the buildings of the Giardini Papadopoli.   Lost art Lost artThe Virgin and Child of c.1465 by Lazzaro Bastiani, in the Accademia since 1812. The church in art The detail above left is from a Bellotto view. Above right is a detail from a Canaletto called The Canale Santa Chiara, in the Wallace Collection in London. The Canaletto drawing which was used by Bellotto oddly omits the pair of tall windows over the doors flanking the main door, and so Bellotto's painting omits them too.

|

||

|

|

||

History The order of the Servi de Maria (Servites) based in Cannaregio were given money in 1338 by Marsilio da Carrara, Signore of Padua, to build a church called Santa Maria Novella on the Giudecca. The church was built on the site of an oratory dedicated to Saint James, and inherited the name. (Until 1999 the local Vaporetto stop was also called San Giacomo.) After a bad patch the church and monastery experienced a prosperous 16th century and both were rebuilt. Before the building of the Redentore later in the 16th century this was the biggest church on Giudecca. Suppressed by the French in 1806, the monastery became a barracks in 1821 and was demolished in 1837 to make way for public housing. Lost art Michele Giambono's panels of a polyptych of Saint James the Greater flanked by Saint John the Evangelist and Filippo Benizi (the founder of the Servites, without a halo as he wasn't canonised until 1671) on the left and the Archangel Michael and Saint Louis on the right, from c.1450, originally in this church, is now in the Accademia, to which it came in 1812 from the suppressed Scuola del Cristo on Giudecca. Giambono was also a mosaicist - his work can be seen in San Marco. Vittore Carpaccio's early Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John, which was after restoration work in 2003 reattributed to him, after having slipped to the status of copy following dubious conservation work in the 20th century and it's withdrawal from display in 1957. It's now back on display in the Correr, and looks flat and unconvincing, presumably because of all the restorations. Veronese's (workshop's?) late Assumption of the Virgin, now in the Accademia, decorated the centre of the ceiling of the refectory here, flanked by two ovals of the  Annunciation and the Visitation,

which are currently in storage there, along with a sections of a frieze

with leaves, putti, and allegorical figures. The two oval paintings were cut down

to rectangles, probably in 1882 when they went to

San Zan Degolà. On the wall was the Feast in

the House of Levi (see left), largely the work of Veronese's

brother Benedetto and his sons Gabriele and Carletto, but the painting was

probably begun by Veronese himself just before he died. It seems to have

been painted to be of a piece with the ceiling paintings mentioned above. Following suppression it

became the property of the Accademia. Since 1910 it has been on loan to

Verona, and since WWII it has hung in the town hall, the Palazzo Barbieri.

It got a much-needed cleaning for the Veronese exhibition held in 2014 in

Verona where it looked fine. Annunciation and the Visitation,

which are currently in storage there, along with a sections of a frieze

with leaves, putti, and allegorical figures. The two oval paintings were cut down

to rectangles, probably in 1882 when they went to

San Zan Degolà. On the wall was the Feast in

the House of Levi (see left), largely the work of Veronese's

brother Benedetto and his sons Gabriele and Carletto, but the painting was

probably begun by Veronese himself just before he died. It seems to have

been painted to be of a piece with the ceiling paintings mentioned above. Following suppression it

became the property of the Accademia. Since 1910 it has been on loan to

Verona, and since WWII it has hung in the town hall, the Palazzo Barbieri.

It got a much-needed cleaning for the Veronese exhibition held in 2014 in

Verona where it looked fine.The church in art Visible in many 18th-century views of the Redentore, to the right (west). A View of the Redentore, Venice, on the Feast of the Redeemer (detail top left) is attributed to Johann Richter and owned by the University of Cambridge. It should be noted, though, that Richter's views are sometimes less than totally topographically accurate. The church is also to be seen in at least four Canaletto views of The Church of the Redentore. Versions are to be found in Woburn Abbey, the Manchester Art Gallery, and a sale at Sotheby's New York in February 2018. One of them moves San Giacomo further to the right, and in the one in the Sotheby's sale the campanile is moved towards the west end of the church. The Manchester version has the clearest view (see detail above right) but the buildings in front of the church in all of them seem to contradict the early-18th- century map below.

|

||

History  Church and monastery founded in 1339 by Bonacorso Moriconi, a merchant from Lucca and occupied by Camaldolesi monks from San Mattia on Murano. The complex stood at the tip of Giudecca, opposite San Giorgio (see the Merian map detail at the start of the Giudecca section above). It was completed in 1344, with the addition of a hospital for the poor in 1369. The church was renovated and consecrated in 1371 by Paolo Foscari, the Bishop of Castello. Once had organ doors painted by Cima de Conigliano. Around 1806 the church was demolished. Lost art A small panel by Giovanni Bellini's workshop of Doge Pietro Orseolo I and his wife Felicia Malipiero at Prayer (see right) is thought to be all that remains of the predella from a lost polyptych painted for this church c.1500-1505. The panel is now in the Correr Museum. Organ doors by Cima da Conegliano and his studio depicting The Annunciation from c.1510-15 are now in the Accademia.

The church in art |

||

|

Sant'Angelo |

||

History History Capuchin monks found refuge here in 1546 when they were expelled from the Redentore by the heretic Fra Bernadino Ochino, returning in 1548 when the monastery was destroyed and the heretic expelled. And here it was that the Carmelites living on Sant'Angelo di Concordia were moved in 1555, and that island then took its present name, Sant'Angelo della Polvere, because the Senate decided to depopulate it due to its unhealthy air and to install a gunpowder depot, it being a good safe distance from places of habitation. The complex was closed down and sold in 1806. The church was reopened and closed again repeatedly in the decades following. In 1867 the convent became a glass works of the Battisti company. The complex was taken over when Junghans expanded their factory in 1943 to make more weapons, at which time the church was demolished, with three altars and some furnishings moved to Sant'Eufemia. The latter included two gilt angels which were placed by the high altar there and which disappeared in 1980. That's maybe one of them in the old photo (right).

|

||

History Initial consecration of the church dates from 1188, with an attached hospice for pilgrims on the way to the Holy Land. In 1222 a monastery was founded by Benedictine nun Giuliana di Collalto, who became the abbess. In 1519 accusations of moral laxity led to reformation and the transfer here of fourteen nuns from Ognissanti. In the 16th century the complex underwent major restoration, with the church renovated by Michele Sanmicheli. Later restoration was carried was the early 18th century by Domenico Rossi and Giorgio Massari. This work resulted in the demolition of Sanmicheli's choir roof, the columns from which were used to make the portico of the nearby church of Sant’Eufemia. (The remains of Giuliana di Collalto where moved to Sant'Eufamia too, in 1822. Her decorated coffin is in the Correr.) Pope Pius VII visited in 1800. Suppression followed in 1810  and the

complex was put to use as a hospital for infectious diseases. It then

passed into private hands and was gradually demolished for building

materials, including the floor which went to the church of

Santa Maria del Pianto. It was finally destroyed in 1882. and the

complex was put to use as a hospital for infectious diseases. It then

passed into private hands and was gradually demolished for building

materials, including the floor which went to the church of

Santa Maria del Pianto. It was finally destroyed in 1882.Lost art Saints Nicholas, Charles Borromeo and Lucy by Palma Giovane, which came from this church, is now in San Pietro Martire on Murano. Filippo Stancari's The Blessed Giuliana di Collalto Receives the Abbey Ring from San Biagio is now in the always-closed church of Spirito Santo. Given it's subject, and the fact of Spirito Santo being a receptacle for art from closed churches, it must have come from this church, surely. The church in art Appears at left edge of Guardi's 1757 View of the Giudecca Canal and the Zattere (see detail below) in the Thyssen-Bornemisza, and more centrally in Johan Anton Richter's slightly earlier view of San Biagio and the church of San Biagio e Cataldo on the Giudecca (see right) which seems to be not exactly accurate, in its positioning of the campanile and adding an imaginary extra church (bearing a slight similarity to the church of Santi Cosma e Damiano) for example. |

||

History A Benedictine monastery founded in 1109 and demolished in 1840. It is left of centre on the detail from the Merian map of 1635 above. The Doges Pietro Polani (1148) and Pietro Gradenigo (1310), who foiled Bajamonte Tiepolo's rebellion, were buried here.

Lost art

|

||

|

|

||

History A church, scuola and hospital founded in 1373 by Corsolino degli Ubbriachi, a Florentine merchant. Lost art Panelling from the scuola here, carved by Pietro Morando, and paintings, were removed and installed in the sacristy of San Pietro Martire on Murano. The Baptism Of Jesus by Jacopo Tintoretto which came from above the high altar here is now also in San Pietro Martire on Murano. An altarpiece St John the Baptist worshipped by Vincenzo Serena by the 'school of Titian' came from here and went there too. Vincenzo Serena having been a Guardian Grande at the Scuola here. |

|

|

|

San Matteo |

San Mattia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

History The church was demolished between 1835 and 1860 following suppression. The chapel of the Santissimo Sacramento was saved from destruction by a Monsignor Giovanni Nichetti, who made it into an oratory in 1848, which still exists. Frescoes in the oratory depict the Trinity, the Four Evangelists, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory, Saint Ambrose and Saint Augustine. Lost art An altar 'in Lombardian style' and the baptismal font, both now in San Pietro Martire on Murano. Ruskin wrote The church no longer exists. |

|

|

Torcello |

||

History

|

|

|

|

The other islands

|

||

| Anconetta | ||

History A small convent church on an island near Marghera was enlarged, beginning in the 1620s, which was when the ceiling paintings mentioned below were installed. The ceiling survived into the second half of the 18th century, despite the walls being stripped and whitewashed in 1772. But the building was closed soon after and demolished in 1855.  Lost art The ceiling paintings mentioned above, all by Leonardo Corona, The Annunciation, The Birth of the Virgin and The Visitation were all lost after the church's demolition. The church in art The island was painted and sketched by Francesco Guardi (see right) and his nephew Giacomo; and by Richard Wilson (see left). The story goes that Wilson arrived at the house of the artist friend he was to stay with, but the friend was out, so Wilson began to sketch the view from his window of the Anconetta.

|

||

History The second and smaller of the two islands passed by the vaporetto from Murano to Torcello/Burano. A small monastery was founded here in 1303 by four Benedictine nuns. It was called San Nicolò and became known as San Nicolò della Cavana . Due to the harsh environment the complex fell into disuse upon the death of the original nuns and In 1432 the bishop of Torcello Filippo Paruta closed it, merging it with Santa Caterina di Mazzorbo. In 1648 two followers of Saint Paul came here and used the island as a hermitage, but they didn't stay long. They were followed by two more equally irresolute hermits. In 1712, with the permission of the nuns from Santa Caterina di Mazzorbo (one of the sources describes 'a brief wrangle') the Venetian Piero Tabacco built a church here dedicated to the Madonna del Rosario. He had been drawn to the island by hearing a bell as he passed in a boat. Suppressed by Napoleon, the complex was demolished in the mid-19th century. In the early 20th century a powder magazine was built, and was used up until the WWII. This is the long roofless ruin which remains on the island. Erosion has resulted in two islands, in fact, with the remains of a guardhouse on the smaller one. There have been plans to bring the island back into use but with no result. An advert online (deactivated on 8th June 2020) shows the island for sale for €300.000 and that it covers 4.500 m². The church in art Giacomo Guardi's Island of San Nicolò della Cavana or Madonna del Monte is in the Morgan Library. |

||

|

History A 14th century Augustinian church and monastery by Pietro Lombardo. A Protestant cemetery was established here in 1719 with Napoleon founding a proper monumental cemetery here post-suppression in 1807. The church was demolished around 1810, which resulted in its works of art being destroyed or sold, mostly out of Italy. In 1835-9 the channel between San Cristoforo and San Michele was filled in to create the current cemetery island of San Michele. Lost art Giovanni Bellini painted Saint Jerome between Saints Peter and Paul for the altar of the funerary chapel of Grand Chancellor Giovanni Dedo in San Cristoforo in 1505. Zanetti said it was in a poor state in 1771 - it's now lost. Another lost Bellini from this church is Saint John the Baptist Between Saint Jerome and Saint Francis with a lunette depicting the Virgin and Child, Saint Clare and Saint Veronica. (see right) which went to the then Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, was presumably destroyed in 1945 in the fires in the Friedrichshain flak tower (Flakturm) where paintings from the Berlin collections were being stored to protect them from bombing. An altarpiece by Francesco Guardi was also destroyed. A Virgin and Child with Saints by Alvise Vivarini is said to be in Berlin, but was not to be found in the Gemäldegalerie when I was there, and may have been the one destroyed in the same fire mentioned above). Also a Virgin and Child with Saints by Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (previously thought to be by Basaiti) painted for the ferrymen of Murano, is now in San Pietro Martire on Murano. A triptych from the late 1550s by Jacopo Bassano for the high altar here, one of the few altarpieces he painted for Venetian churches, is now only appreciable from its central panel, depicting Saint Christopher, carrying the Christ Child, now in the Havana Museo Nacional

The church in art

|

|

|

|

History The first and larger of the two islands passed by the vaporetto from Murano to Torcello/Burano. The name translates as Saint James in the Marsh. It was in 1046 that Giovanni Trono from Mazzorbo was given some marshland by Orso Badaoro to build a hospice to house travellers, passing pilgrims and sailors caught in storms. In 1238 the complex/convent passed to Cistercian nuns who enlarged the complex. They left around 1440 at which time only two nuns remained, moving to Santa Margherita di Torcello, another Cistercian nunnery. In 1456 lepers from San Lazzaro were moved here temporarily, to make way there for plague victims. When they returned Franciscan friars settled here, lead by friar Francesco of Rimini, who collected alms towards the restoration of the complex, and then returned to Rimini having removed fixtures and fittings too. This misconduct resulted in the monastery being joined with the large and wealthy Frari house, resulting in much restoration and enlargement, including the building of a new church in the late 15th century. The friars were still hosting guest rooms for travellers and pilgrims (foresteria) at this time. The convent was in a state of ruin by the end of the 18th century, with the friars from the Frari renting it out to workmen, and was then suppressed by Napoleon in 1810 and the church demolished. The island was put to military use until it was abandoned in 1961, with two buildings having been used as a powder store, of course, and what was left was restored by the Magistrato alle Acque. The church is reported as one of the buildings converted to military use. It was said that before the sale that the island had seven crumbling 19th-century buildings - four long-crumbling and three restored in the 90s which were then also in a poor state. Having been put up for sale in 2016, originally to help repay Italy's national debt, along with 49 other 'historical assets, the island was eventually bought by arts collectors Patrizia and Agostino Re Rebaudengo. They are legally prohibited from building a hotel, say, only being allowed to use the island for community and/or cultural use. It has been used to host Biennale exhibitions and did so in 2022, before work was to continue ahead of a fuller opening, possibly in 2024. The fact that the island is located along the migratory routes of some birds once suggested another possible use. Ampullae find An early-14th-century ampullae was dug up  here here

by an archaeological team from Ca’ Foscari excavating to find the original convent buildings in the early 2000s. It is one of only a few found in Italy of this type, and the only one to be recovered from a stratigraphical excavation. Ampullae were small flat flask-like lead containers which pilgrims tied to their belts, or carried, which contained oil from the lamps that burned by the tombs of the saints in Europe and the Holy Land. The Duomo Museum in Monza was where I first learned about them, as they have a fine and well-displayed collection. The church in art San Giacomo in Paludo by Giacomo Guardi (see right) is in a private collection. The staffage is thought to have been painted by his father Francesco. The drawing from c.1779 by Francesco Tironi (see above right) is in the The Met in New York. |

|

|

History HistoryCalled Saint George in the Seaweed, this was an early - 1020 - Benedictine establishment. Monks from here moved to San Giorgio in Braida in Verona in the 15th century(?) The Blessed Lorenzo Giustiniani then founded his congregation of canons called the Turchini here (so named for their Turkish blue/green colour robes) which took over the Madonna dell'Orto in 1462. They were an order who didn't believe in building new churches but were committed to occupying old ones. Following a fire in 1716 the reconstructed buildings were used to house political prisoners after the fall of the Republic. The church and monastery were suppressed in 1806 and the church demolished c. 1820, The island then descended into various military uses, including a training base for German divers in WWII, and subsequent neglect. Ruskin wrote Unimportant in itself, but the most beautiful view of Venice at sunset is from a point about two-thirds of the distance from the city to the island. From the island itself, now, the nearer view is spoiled by loathsome mud-castings and machines. But all is spoiled from what it was. The Campanile, good early Gothic, had its top knocked off to get space for an observatory in the siege. Lost art An Adoration of the Shepherds by Cima da Conegliano was here by 1497, but is now lost. The church in art The Island of San Giorgio in Alga by Francesco Guardi (see above). |

||

|

|

|

|