|

|

|

Frari |

||

|

History The first church here was said to have been an oratory built in 726. dedicated to Saint Cecilia and belonging to Benedictine nuns. Rebuildings followed in 926, 1106 (after the great fire, when it was made a parish church and changed its name), 1205 and 1350, with this church consecrated in 1376. Rebuilding in the early 17th century brought the church to its current internal appearance, this work finishing in 1663. A portico was demolished in the 19th century when the church acquired its current external appearance. 'Important' relics of Saints Cecilia and Cassian are kept here. The church Outside it just looks like a big box. The rio-facing façade misses its portico and is encroached on by adjoining buildings. It retains its Byzantine-era doorposts, possibly from the original church. Entry is usually now via the small side-door onto the campo. Interior The interior makes up for the lack of façade and the very plain exterior, being highly decorated but managing to stay this side of exhausting, despite having an ceiling-high altar by Meyring and Nardo, the first being responsible for the decoration of San Moise, the church that makes you say 'blimey!' His work here is relatively restrained, as are the rather splendid Venetian chandeliers. The use of pale colours generally lightens the interior, even the heavily-decorated ceiling, with its paintings by a Tiepolo-follower called Costantino Cedini, including one of Saint Cassian in Glory. The late Tintorettos here are exceptional too, with a Crucifixion, a Resurrection and the Descent Into Limbo ranged in sequence around the chancel, all commissioned by the Scuola del Santo Sacramento who had taken on responsibility for its decoration, and all restored in 1996. Saint John the Evangelist in the famous and unusual side-view Crucifixion (1568) even directs the Virgin's attention comic-strip-like into the next 'frame' - the Resurrection with Saints Cassian and Cecilia (1565) over the altar, which features Saint Cassian on the left and Saint Cecilia on the right, the church's previous dedicatee. Then in The Descent into Limbo (1568) Jesus harrows hell and frees Adam and a very sexy Eve, with the members of the commissioning confraternity peering from the darkness behind. Tintoretto's first studio had been in the Campo San Cassiano, from around 1537/8 to 1547. He had been born nearby and lived here for the first 30 years of his life. The nave of the church has three altars each side with three paintings between them, the best by Rocco Marconi, a John the Baptist with Saints Peter, Paul, Mark and Jerome looking more than a bit Bellini, of whom he was a pupil.  You may have to ask, but access to the small chapel half way along the left hand wall is worth it, as it is an odd little jewel-box of a room - all marble and inlaid semi-precious stones. Commissioned in 1746 by Abbot Carlo del Medico it has an altarpiece (1763) and ceiling fresco by Giambattista Pitoni. It also contains an early-18th-century painting of the Martyrdom of Saint Cassian by Antonio Balestra, and yes those children are stabbing him with pens. Cassian of Imola was a teacher in the 4th century, martyred by his pupils using iron pens, used to write on wooden or wax writing tablets, which they also whacked him with. That this martyrdom was ordered by a judge (in punishment for refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods) dilutes the cruelty a little, but the fact that two hundred of them joined in, some carving letters into his skin, does not. He became the patron saint of schoolteachers and in 1951 a congress of Italian shorthand-writers asked that he be made their patron saint too, a wish which Pope Pius XII granted. Campanile 43m (140 ft) electromechanical bells Its sturdiness suggests that it may have been built as a defensive tower and later acquired by the original church. Built in 1295 with a Gothic belfry added in 1350. Lost Art The San Cassiano Altarpiece by Antonello da Messina (1475/6) was commissioned by Pietro Bon, the Venetian counsel in Tunisia, and was housed in the old Gothic church here. Sansovino in 1581 describes it over the first altar on the right. It introduced oil painting to Venice, probably, and was influential in introducing the layout of the typical unified-space 'Venetian' altarpiece. But whether it influenced Giovanni Bellini, with its Flemish use of glazes, or whether it was influenced by Giovanni, is also debated. Arguments as to whether this painting or Bellini's lost Saint Catherine of Siena altarpiece from San Zanipolo was the first unified pala produced in Venice also still rage. As do arguments as to that work's influence on the San Cassiano altarpiece. It was dismembered in 1620, during the rebuilding - its disappearance is first mentioned in 1648 - later appearing in the collections of Venetian merchant Bartolomeo della Nave and the Duke of Hamilton. Five fragments reappeared in the collection of Archduke Leopold William in Brussels, attributed to Giovanni Bellini. In 1700 the three fragments that remain (there were originally eight saints) (see below right) found their way to Vienna, and are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. The central Virgin Enthroned was identified by Berenson in 1917 as part of this altarpiece and the two other remaining fragments, showing Saints Nicholas of Bari and Lucy on the left and Saints Dominic and Ursula on the right, were found in the galleries depot in the 1920s. Engravings by Teniers of two further fragments exist Almost lost was the Tintoretto Crucifixion. In Venice in 1852 John Ruskin wrote a letter asking for £7000 from the National Gallery in London to acquire it 'for the nation'. The Tintoretto Marriage at Cana was included in the deal, for £5000. He never got the money and so the paintings remain in their Venetian churches. He presumably sold this shameful asset-stripping to his conscience because his opinion was that the Tintorettos were all that this church had going for it (see below). Ruskin wrote 'This church must on no account be missed, as it contains three Tintorets, of which one, the "Crucifixion," is among the finest in Europe. There is nothing worth notice in the building itself, except the jamb of an ancient door (left in the Renaissance building, facing the canal), which has been given among the examples of Byzantine jambs; and the traveller may therefore devote his entire attention to the three pictures in the chancel.' Of The Resurrection he says 'It is not a painting of the Resurrection, but of Roman Catholic saints thinking about the Resurrection'. And of the low viewpoint of the Crucifixion: 'The horizon is so low, that the spectator must fancy himself lying full length on the grass, or rather among the brambles and luxuriant weeds.' Henry James wrote in Italian Hours, that standing in front of Tintoretto's Crucifixion here... "It seemed to me that I had advanced to the uttermost limit of painting; that beyond this another art—inspired poetry—begins, and that Bellini, Veronese, Giorgione, and Titian, all joining hands and straining every muscle of their genius, reach forward not so far but that they leave a visible space in which Tintoret alone is master." Also that 'No painter ever had such breadth and such depth…Titian was assuredly a mighty poet, but Tintoret–well, Tintoret was almost a prophet'. Local colour In 1488 this church's entrance was ordered to be chained shut, and the porch of Santa Maria Mater Domini was sealed off, 'after the twenty-third hour' to 'stop sodomites using it as a meeting place'. Local pastry shops were also said to be dens of such iniquity. The funeral procession of Caterina Corner, the ex-Queen of Cypress, in 1509 started here and made its way over a bridge of boats to the church of Santi Apostoli where she was buried. Tintoretto was born in the parish of San Cassiano in 1519. His baptismal certificate was lost in a fire, but we can assume that he was baptised in this church and attended it in his childhood. Campo San Cassiano was the site of the first public opera house in the world which opened in 1637. It was demolished in 1812 having been badly damaged by several fires.

The church in fiction

Opening times |

|

|

|

History Traditionally said to be the oldest church in Venice. An inscription on the left-hand pillar in the chancel says 421 but legend goes even further and claims that the church was consecrated at noon on the 21st March 421, this being the date that the republic used to celebrate as Venice's birthday, it being also supposedly the date of the Annunciation to Mary. Information about the rebuilding is vague. Nothing ancient remains - the current church was built sometime during the reign of Doge Domenico Selvo (1071-84) and consecrated in 1177 by Pope Alexander III. It survived the fire of 1514 which destroyed most of the market, but must have been damaged as it underwent considerable restoration in 1531 (according to a plaque by the entrance) and again in 1599-1601. This latter work improved the lighting and installed some heavy baroque altars, but the original mosaics were lost. The choir on the inside façade was removed in 1933. This has always been seen as the 'market church' and has altars dedicated to various guilds of merchants and craftsmen. A cross-shaped inscription from the 12th century on the outside of the apse (see below right) tells merchants to be honest in their dealings and precise in their weights. The church now hosts concerts where Vivaldi's Four Seasons are performed most nights. The church The façade is dominated by one of only two wooden Gothic church porches to remain intact in Venice (the other being at San Nicolò dei Mendicoli - the rest were removed from the 16th-century for encouraging immoral behaviour). It was restored in 1958. Also the large and ever-wrong 24-hour clock above the 17th century windows, which was put up in 1410 and restored in 1749. Above is the bell gable topped by a statue of Saint James. Interior Hemmed in by the market bustle, this is a dinky little Greek-Cross shaped church with a dome, some charm, but no great art. Most of the city's original 70 parish churches would probably have been this shape originally, if not this small. This one has had much reconstruction too, of course, but retains its original shape. The Greek marble columns with their Veneto-Byzantine capitals remain from the 11th-century church. Campanile The original was destroyed by fire in 1514. The current Roman-style tower was built in 1749. Under the bells is a Gothic relief of the Virgin and Child from the early 16th century. Ruskin wrote It has been grievously restored, but the pillars and capitals of its nave are certainly of the eleventh century; those of its portico are of good central gothic. E V Lucas wrote The little church of the market-place—the oldest in Venice—is S. Giacomo di Rialto, but I have never been able to find it open. Commerce now washes up on its walls and practically engulfs it. A garden is on its roof, and its clock has stopped permanently at four. From “A Wanderer in Venice” 1914. Lost art According Augustus Hare's guide book to Venice of 1904. In 1664 it possessed 'good pictures by Lanfrancus and Marcus Veccelli, old Titian's nephew and scholar'. Local colour  Opposite the church you'll find (usually hidden behind piles of boxes and rotting vegetables) the 16th-century granite statue of Gobbo di Rialto (the Hunchback of Rialto) - a crouching naked bearded man supporting a flight of steps, bearing a plaque, up to the top of a granite column known as the Pietra del Bando (see right). The Republic's decrees where once read from this pedestal and men convicted of petty crimes would run the gauntlet of beatings naked from the similar Pietra del Bando in Piazza San Marco to this statue where the punishment would end when the criminal kissed the statue. Shakespeare is said to have named the clown Gobbo in The Merchant of Venice after the statue, sculpted in 1541 by Pietro da Salò. The church in art Canaletto's early San Giacomo di Rialto (see below left) is in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. There are also several later drawings by him, including one in the Courtauld Gallery in London, which vary the number of columns in the portico. Opening times Monday to Saturday: 9.00 to 5.00 Sundays: closed A (recently added) Chorus Church, but entry is still free, presumably because it's so small and dominated by the bright concert-ticket desk. Vaporetto San Silvestro or Rialto map |

|

|

The old photo in the centre

shows a strangely changed facade that I (and others) can find no

documentary explanation for. |

||

|

San

Giovanni Elemosinario |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Opening times |

|

|

|

History This church, dedicated to the apostle Paul, was founded in 837 by the doges Pietro Tradonico and Orso Partecipazio and rebuilt in the 12th and 15th centuries. Some heavy-handed restoration, additions and losses (including a mosaic-covered chapel and a silver Byzantine altar-front) during work in 1804 by David Rossi were partly reversed in 1927 revealing, for example, the 15th-century wooden ship's keel roof and restoring the rose window which dates from the same period.

The church Interior

Saint John of Nepomuk

|

|

|

|

History One of Venice's four plague churches, along with San Giobbe, San Sebastiano and the Salute, this church was built 1489-1508 by Pietro Bon for the Confraternity of San Rocco, along with the scuoletta to the right of the church's façade. The confraternity had been founded in the plague year of 1478 by a group of prominent families. It had thrived following its stealthy 'translation' of the saint's body from Volghera in 1485 by two monks, its mission being to help the poor and sick, particularly plague victims, and so this church was built to house these remains. This original church can be seen on the Barbari map and the engraving of the church by Carlevarijs (see below). Extensive rebuilding, occasioned by the danger of collapse, by Giovanni Scalfarotto from 1725, kept only the apse, the (repositioned) side door and a window from the Bon church. Following the plague of 1575/6 the Doge and Signoria would visit San Rocco on the saint's day to give thanks for his intercession. The church The façade was erected in 1765-71 by Giorgio Fossati and Bernardino Maccaruzzi to match the façade of the scuola. The statues flanking the doorway are by Giovanni Marchiori, who has more works inside, those above are by Gian Maria Morleiter. The statues depict four Venetian saints: Lorenzo Giustiani, the first patriarch of Venice; Gregorio Barbarigo, a bishop of Padua and a cardinal; Pietro Orseolo, doge from 976-978; and Gerardo Sagredo, who became a patron saint of Hungary. The side door and rose window are the work of Bon - the window had been on the façade, as can be seen in the prints below, but was moved around the side when the baroque façade was built. Both door and window were restored 2000-2001. Interior Aisleless, with two altars each side - all matching and separated by large panel paintings. The first altars, left and right, have altarpieces by Sebastiano Ricci. The six highlight Tintoretto works are in the choir, which has a painted ceiling and vault by Giuseppe Angeli. Tintoretto's Saint Roch Cures the Plague Victims, the first, is from 1549, and so while the Scuola was still bare of paintings, his fee was probably low, but accompanied by a promise of membership of the scuola. This is the painting which Vasari grudgingly admitted had 'some nude figures very well conceived and a dead body in foreshortening that is very beautiful'. Saint Roch in Prison Comforted by an Angel is later, dating to 1567, by which time Tintoretto was an established member and busy painter of the Scuola. Also by him on the south wall of the nave here is Christ at the Pool of Bethesda, painted in 1559 for the doors of a reliquary cabinet. It is opposite Saint Christopher and Saint Martin on Horseback by Pordenone, who had also frescoed the apse and cupola before he died in 1539 and Tintoretto took over. On the baroque high altar are the remains of Saint Roch himself, brought here in 1485, and a statue of him, the altar and statue both being by Bartolomeo Bon. Impressive large panels by Giovanni Antonio Fumiani on the left wall and the nave ceiling.

Opening times Daily 9.30 - 11.30 &

3.00 - 5.00 |

|

|

|

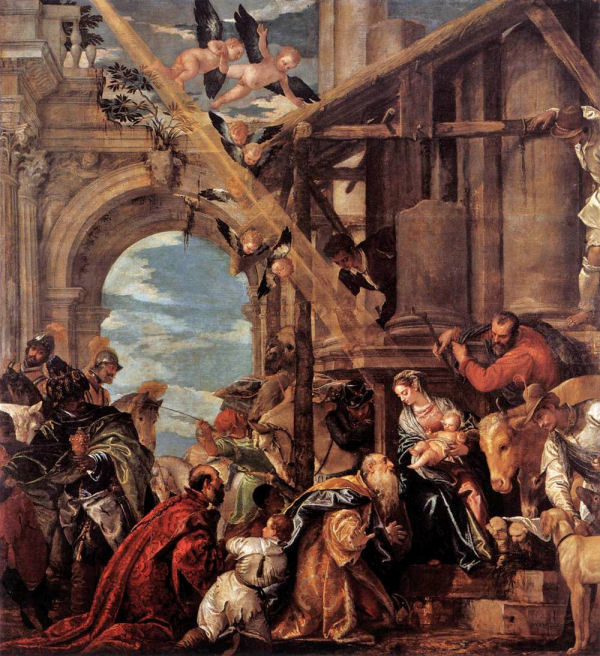

History Founded in the 9th century, this church was rebuilt in the first half of the 15th, being consecrated in 1422 and incorporating the nearby oratory of Ognissanti. There was further rebuilding in the first half of the 17th century and then again, and more comprehensively, in 1836-43. A large part of the altar of Saint Joseph, including a cornice and three angels, had collapsed on the night before Easter Sunday 1820. Subsequent surveys showed that the church was in danger of falling down. Rebuilding began in 1836 to plans by Lorenzo Santi, and was continued by Giovanni Meduna, following Santi's death. Reconsecration took place in 1850. In 2010 the church was closed due to falling bits of ceiling. It then acquired the appearance of a building site, with barriers all around, netting under the ceiling inside, and the campanile sheathed in scaffolding, which work was finished by May 2016. Aside from the campanile no trace remains of the earlier structures, except for a column fragment with a capital of Veneto-Byzantine style built into the wall facing the Rio Terrà. The church The façade dates from 1909 and is the work of Giuseppe Sicher. A 17th-century statue of Saint Sylvester stands in the niche over the door. Through an iron gate to the right inside is the Scuola dei Mercanti di Vino, which has a chapel upstairs with 18th-century frescoes, depicting three episodes from the life of Saint Helena, by Gaspare Diziani, a pupil of Ricci. You'll need to ask the sacristan to let you in. The scuola of the mastellai (coopers) was once attached to this church too, but was destroyed around 1820. Interior A very unarchaic church mostly dating from the early 19th century when it was rebuilt in a relatively unembellished neoclassical style. It's big and has a flat ceiling painted to imitate coffering. Art highlights A lot of the paintings the church once contained have been lost, but there's still Tintoretto's late and impressive Baptism of Christ of 1580-82 (reinstalled after the 19th-century rebuilding, but not over its original altar, and restored in 2004). Opposite is an appealingly bright and Bellini-esque Saint Thomas Becket Enthroned by Girolamo da Santacroce from 1520, but with a couple more dingy flanking saints (John the Baptist and Francis) added in the 19th century by one Leonardo Gavagnin. Each of these paintings is the wrong size and shape for the spaces they inhabit, suggesting that their reinstallation into the rebuilt church was forced on the architect late in the process. Lost art  Veronese's fine 1573 Adoration of the Kings (see right) now in the National Gallery in London, was painted for San Silvestro (for the Scuola di San Giuseppe - it hung to the left of their altar, which already had an altarpiece) where it remained until the 19th century rebuilding, after which it was found to be too big, or so the official account goes. The fruits of more recent investigations have suggested that the decorative plans post-rebuilding never included the Veronese and it seems that the fact of money being sorely needed, and that ecclesiastical fashions had changed, may have had more than a little bearing on the sale. During restoration work on this painting prior to the big Veronese exhibition at the National Gallery in 2014 small holes were found in the paint in a strip along the top, which turned out to have been cause by splashes of bat urine. Campanile 47m (153ft) manual bells Destroyed by an earthquake on 25th January 1347, rebuilt 1422, restored 1840. Hear the bells Ruskin wrote Of no importance in itself, but it contains two very interesting pictures: the first, a "St. Thomas of Canterbury with the Baptist and St. Francis," by Girolamo Santa Croce, a superb example of the Venetian religious school; the second by Tintoret, namely "Baptism of Christ". Local colour The artist Giorgione died in the house opposite the church door (no. 1022) (the Palazzo Valier) during the plague of 1510. He was said to have painted frescoes on the palazzo wall to advertise his skills, of which traces were still visible in the early 20th century. But Lorenzetti says that this is only the 'supposed abode' of the painter, who 'lived instead perhaps' at no. 1091 to the left. Opening times Monday - Saturday: 7.30-11.30, 4.00-6.00

Vaporetto

San Silvestro |

|

|

| San Tomà | ||

|

History Dedicated to Saint Thomas the Apostle, the church was founded in 917 and restored in 1395. It was enlarged in 1508 with more work in 1652. The façade from the 1652 rebuilding, by Giuseppe Sardi, a pupil of Longhena, was replaced (as it was about to fall down) with a classical façade by Francesco Bognolo in 1742-55. In a city not unobsessed by holy relics, this church is said to have once had 10,000 saintly bits and a dozen intact holy corpses. It was a parish church until 1810 and taken over by Franciscan friars from 1835-1867. In 1970 the by then deconsecrated church was converted for use as a workshop for the restoration of paintings, specifically smaller works to take the strain off of San Gregorio, which had been converted for such use in 1968. Closed in 1984 for restoration and yet to reopen. Exterior On the left side of the church there's a marble relief of the Madonna della Misericordia probably taken from church of Santa Maria della Carita (now part of the Accademia Gallery) at the end of the 19th century. Above the side door on the Campiello del Piovan is the tomb of Giovanni Priuli of 1375 (see photo below right) which was moved here from inside the church when the façade was rebuilt in 1742.

Interior |

|

|

|

This 1703 print by Carlevarijs is presumably of

San Toma's previous façade, |

||

|

Art highlights? |

|

|

|

|